The Green Imagination in Board Game Landscapes

Try to remember the landscape of a board game you’ve played: Clue’s opulent hallways, the poor house I always ended up with at the end of a game of Life, chess’s austere black-and-white battleground. In the last lonely year, I’ve turned to board games as a way of having fun with my partners at home. While playing, however, I started noticing how board games could tell environmental stories.

Indeed, there is a thriving market for games that try to use their rules to evoke environmental themes. Games about birds, climate change, and even anticolonial resistance have become popular in the last half-decade or so, but I wanted to dig further. I was after games that didn’t just tell environmental stories, but ones whose rules could create social stories of environmental history.

What I was looking for was a game where the shared landscape of the board mattered beyond decoration. I wanted games whose boards, whose ecological maps, shaped player actions and did not portray nature as outside human history. Rather, the games should involve the land and water in their unfolding drama. This entanglement would give players a sense of stakes, emotional bonds with the land that could evolve as the story moved on and players asserted themselves within the environment of the game.

In testing out games to write about, I found two, Root and Oath, both designed by academic-turned-game-designer Cole Wehrle. Wehrle has always been intentional about the role of politics in all of his games. From historical works like Pax Pamir and John Company—both morally gnarly games about the politics of empire—to fantasy designs like Root and Oath, his work tries to highlight and unfold the tensions between ruler and ruled. While none of his work is “green” in theme, Root and Oath both use contested landscapes to tell environmentally keen stories. In jockeying for rule of these games’ beautiful worlds, players become invested in these fantastical landscapes and develop a sense of shared—if hostile—engagement in these worlds.

The Multiple Meanings of the Woodland in Root

Let’s talk about Root. Root is a war game staged in a Redwall–esque woodland. Players play human-like animals, fighting each other for dominance of a shared map. Armies of cats, birds, otters, moles, and mice scurry from clearing to clearing as war overtakes the woodland. Each faction has a set of habits and lifeways, which makes gameplay very different for each of the game’s eight factions. By the end of the game, each player has understood not just the different moves they need to take to win, but also the way that each faction “sees” the woods. An awareness of landscape is a crucial part of play. To show what I mean, let’s take two factions, the industrious and enterprise-minded Marquise de Cat and the otter-staffed Riverfolk Company.

For the cat player, the map plays how it looks. Within the story of the game, the cats, as the current rulers of the woodland, might have even made the game map. To them, every path is just a path and every building slot should be filled. They begin with a warrior on every space, and their actions all concern the map itself, with little hidden information. They can win by juggling supply trains, building up their recruitment and labor, and massing troops.

Every cat player looks at the landscape as a vessel for buildings that are both power and burden. The Marquise might be the “fat cat” of the woods, but her forces act slowly and without guile. They are, in the spirit of James C. Scott’s high modernists, trying to build an orderly woodland. Like the mid-twentieth-century social engineers Scott describes, the cats’ ambitions are not merely to govern the woodland denizens, but also to reshape the people and landscape in their own image.

Board game geography forces players to think politically about what they’re doing with the landscapes.

But the beauty of Root is that every player feels differently about the map. By far the slipperiest force in the woods is the Riverfolk Company. Staffed by adorable otters, the Company also sees the woodland as a source of profit. But their landscape is very different. For one, otters can swim up and down the river on each map. And unlike the cats, the map looks most appealing when the relationship between players is more uncertain. The trick with the otters is that they are not an army, at least not at first. They sell off their cards like goods and can rent their soldiers to other players. Slipping into profitable trade niches, otters succeed by moving up and down the river to seek new markets. Instead of ruling and defending that rule, they seek to undermine established orders.

The map is far less straightforward from the otters’ perspective. An otter player sees clearings not as places to build but as places where other players can do business with you. By traversing the water, the otters see and move through the forest in a manner unlike any other army. Further, by setting prices for their goods and talking to other players like the slippery characters they are, they try to make themselves indispensable before eventually buying their way to victory. Their woodland is less linear, less clear.

Root does a beautiful job of showing players how one ecology, one map, can hold two vastly different meanings. By trying each army, you develop awareness of different—sometimes ugly—views of what nature should be and how to make use of it. No scrap of woodland is empty wilderness—all of it is political.

Of course, the specific politics of the game’s many factions are hardly environmentalist. What I admire about Root is that it places these settler, mercantile, imperial, and colonial forces in a vibrant setting that makes players intently aware of the map and how their faction interacts with it. This is why Root is fascinating to me: despite using a theme only tangentially related to environmental issues, the play experience of the game ends up revealing how “modernizing” or colonial power structures attempt to overwrite the board’s ecosystem for their own ends. While many environmental games foster an admiring stance toward nature, Root shows how compelling board game geography forces players to think politically about what they’re doing with the landscapes in which they find themselves.

The Shifting Landscape and History in Oath

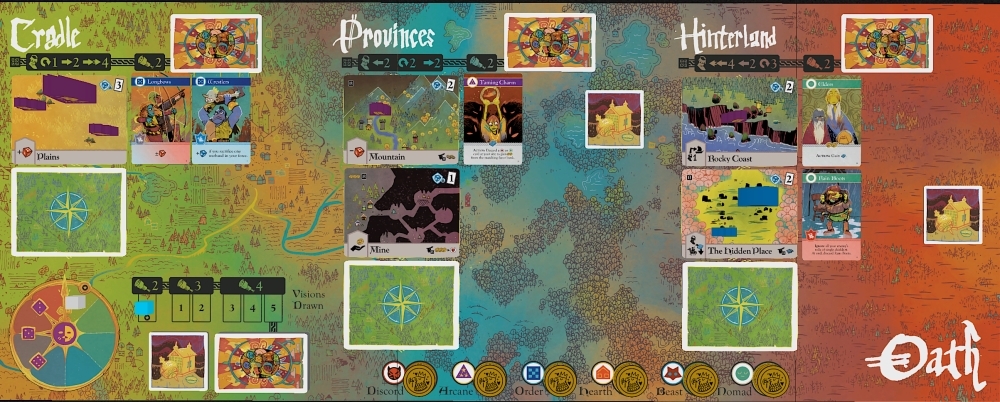

Let’s twist the story and talk about Oath. Oath is, like Root, a game about players struggling to rule a shared land. However, while Root spans a relatively short period of time in a static landscape, Oath plots generations of time and shows how both kingdom and landscape change together—or grow apart.

The key “hook” of Oath is that every game after the first one is played in the kingdom that is built in the game before. To do this, players record the results of each game in Oath’s “chronicle” or historical record. So if your first game ends with the winner only ruling a desert and a strip of coastline, your next game will begin with those sites in play and the rest of the game’s world unmapped. If the last game’s winner seized a sprawling empire, on the other hand, the land you know at the beginning of the next game will be much bigger as well. Landscapes change their significance and can even fall off the map as history moves on.

In Oath, the kingdom is always tied to the land and its people. Most of the game’s landscapes can be populated by denizens with whom a ruler worth their salt will have to curry favor. Oath’s lands are rarely lacking in people: there are no empty lands or wild frontiers. The game’s rules keep the game’s kingdom constantly changing. Centers of power can shift from fertile valleys to nomad-held steppes or even the gambling halls of an ancient city. As players keep playing and write new chronicles, the game also shows how built environments and topography shape how players can exert power. A kingdom based on a set of interconnected coastlines might be fleet and bendable, while a kingdom that has ramparts in the mountains might grow insular, pulling into itself like a turtle. You feel like the world itself has a character—and a character arc.

Even though Oath is a knotty bundle of systems, the rules are easy to learn. These rules teach players how it feels to be part of a system. Every move you take affects the world of the game itself, and you can clearly trace the chain of events across the game’s chronicle. History, for Oath players, becomes something they’ve touched. They’ve felt, so sharply and painfully, the consequences of their actions. As in history outside the game, the course of events—and therefore the shape of the world itself—emerges from the intersection of place, time, force, and luck. And it all takes place within a group of people prodding and listening to each other.

Board Game Landscapes Provoke the Green Imagination

In Root and Oath you feel the power of board game storytelling. You see how different groups see the world’s environmental elements in different ways in Root. Grabbing the solid wooden pieces and moving them lends narrative heft to the world that stirs the imagination. In Oath, the history of the world evolves with landscapes exerting power over the world, not just on a static “natural” backdrop.

Of course, neither game is beyond criticism. Games that derive drama from players using force and guile to assert dominance are not new. Both Root and Oath involve the simulation of war and colonialism, the latter of which has been a lazy thematic skin for games for a long time.

As in history outside the game, the course of events—and therefore the shape of the world itself—emerges from the intersection of place, time, force, and luck.

Nevertheless, I find that Root and Oath still have an important place in the ongoing discussion about how games should relate to colonialism. Though neither game takes a strong moral stand against colonialism, both are, to me, very historically aware and invite players to think about how power works in history. These games have an intentionality and nuance to them that contrasts with blithe appropriations of colonial history in games like Puerto Rico, Mombasa, and Settlers of Catan. They are games with something valuable to say about how colonialism works, and they do not try to soften the often-ruthless implications of their premises. While that means they are going to generate game states that force players to do morally and politically disgraceful things, Root and Oath represent much more thoughtful takes on historical conflict than what most of the tabletop gaming space typically offers.

The other reason these games avoid feeling exploitative is that they rarely generate narratives of virtuous “progress.” Root might always start with the cats in charge of the forest, but despite their initial power they are just as likely to lose as to win. Maybe the rebel mice or conspiratorial crows or enterprising otters will win—everything is highly unstable and contingent.

In Oath, empires can last many games but might evaporate within a few turns. There is no finality, no historical “goal.” There is conflict, yes, and a clear winner at the end of every game. But the game does not validate empire, and in fact makes it feel like power flows like sand through the ruler’s fingers. The fragility of human control over the land and water feels palpable, which is why the setting of the world comes through so strongly despite the fact that these games place players in the role of conquerors. The idea that power, even strong and corrupt power, is always temporary, is strangely comforting to me in these troubled times.

Given the weight of the problems we struggle with in our world, playing games, no matter how thought-provoking, might seem trivial. For me, though, play is core to how I relate to the world. To love the world is to play.

I might not be able to teach my cat, or the alley cats who drop into my backyard, to play Oath. I can’t take my box of Root to the local willow tree and make it understand how the wood in the box makes me feel grateful to trees. When I’m down, feeling guilt or self-hate, I try to play. Root and Oath, with their graceful way of pulling me into an ongoing story, are what I need. They’re ways of affirming my relationship to other people, to myself, and to the world around me. Though any game would do, I’m much better off having games that provoke my “green” imagination.

Like me, anarchist writer Aragorn! (whose name is stylized with an exclamation point) thinks of play very highly: “Anarchists are either people we enjoy playing with or they should return to the gray” (emphasis mine). Let it be no different for environmental scholars and activists! Making the world we love will be playful or it will not be successful. We will win by playing, by making the world a haven for what we love and inviting more of the world to join in. In looking at board game boards and their pretty landscapes, we might find ourselves already stepping toward the world we want.

Featured image: Otters stationed at the river, ready to set up a trading post or slip down the river in the Root board game landscape. Photo by author, May 2021.

All photographs and screenshots by Evelyn Ramiel.

Evelyn Ramiel (xey/xeir) is a content editor for Environmental History Now. After completing an M.A. at York University about human-microbe relations on Japanese warships, xey are writing a dissertation on the ecological and animal history of Japanese character merchandise, also at York University. Xeir last contribution to Edge Effects was “An Ecological Case for Cuteness” (December 2020). Website. Twitter. Contact.

You must be logged in to post a comment.